We heard some extraordinary concerts in January in New York. I heard the New York Philharmonic, conducted by Alan Gilbert, in a performance of Stravinsky's "Rite of Spring". We heard Gilbert conduct this three years ago, and thought it was amazing. I went to hear it again, with some trepidation, knowing that the second time would never be as good. Well, it was even better. I marveled how clearly every single line of Stravinsky's score stood out, how every sound was heard, all without sacrificing any of the drive and energy which the piece needs. It really is an astonishing work; it still sounds audacious and revolutionary. And Gilbert, after returning to the stage a number of times after the deserved standing ovation, picked up the score and waved it at the audience.

The concert opened with a work by Ottorino Resphigi, who in the 1930's denounced Stravinsky's music. The only pieces of his that normally get played are the ones with "fountain" or "Rome" in the title. The piece, "Church Windows", was supposedly inspired by the composer's encounters with Gregorian chant. I couldn't hear anything that sounded like Gregorian chant, except for a lot of stepwise motion in the melodies. Really a lot of stepwise motion. What I heard was a lot of bland melodic content and some bombastic orchestral climaxes. There was even an organ at the end for extra bombasity.

There was also the premiere of a new violin concerto by Magnus Lindberg, a former holder of the New York Philharmonic Resident Finnish Composer Chair, a position now held by his friend Essa-Pekka Salonen. I have liked Lindberg's earlier music; it is brash, energetic, and lively. Lately he has become much in demand by orchestras, as he writes reasonably accessible music. I found the volin concerto to be uncomfortably perched in between the music of his earlier period and some sort of neo-romantic evocation of the grand traditions of violin concertos. There were some striking moments, but also a great deal of note-spinning without great purpose. The contrast was striking when the "Rite of Spring" followed; Stravinsky does not waste notes.

The next night heard the most sublimely beautiful and moving contemporary piece I have heard in years, a piece entitled "let me tell you" by the Danish composer Hans Abrahamsen. It was performed by the Cleveland Orchestra under Franz Welser-Most; the vocal soloist was the extraordinary Barbara Hannigan, who we last heard in last summer's performance of the opera "Written On Skin". The piece is based on a novel by the music critic Paul Griffiths; the novel uses only the 465 words used by Ophelia in Shakespeare's Hamlet. (A game-like restrictive procedure similar to those that the French writer Georges Perec and the Oulipo group used; Perec was famous for writing a novel without using the letter "e") The text is not, though, some sort of mad scene type of thing, but rather a series of short fragments, mostly thoughts about time and memory, and very poetic. The orchestra is used sparingly, but in a very colorful fashion. Hannigan's performance of the vocal part was truly extraordinary; her effortless high notes and amazing ability to blend in with the orchestral textures was exemplary. (Apparently, there is a recording out, in which her voice is miked so as to be quite distinct from the orchestra. In the live performance, part of the effect was hearing her voice blend in and out with the solo instruments in the orchestra.) She sang from memory (a thirty minute piece) and her obvious commitment to the score was striking. She and the composer received a prolonged standing ovation after the performance, a distinction for a contemporary piece both rare and richly deserved.

The program stated that the program was dedicated to the memory of Pierre Boulez; it's too bad that the other piece on the program was Shostakovich's Fourth Symphony. Boulez apparently detested Shostakovich's music, and he never conducted any of his music. Maybe some day they will honor the memory of the composer by actually playing his music!

(My dream concert: Barbara Hannigan singing Boulez's "Pli Selon Pli". That would surely be the best way to honor his memory!)

So the other half of the program was Shostakovich's Fourth Symphony, a sprawling piece, well over an hour long. To my ears, the piece presents a relentless, nervous energy; it seems to go on and on without any clear sense of direction. I resisted at first, and then eventually went with the flow. There were many striking moments, but at the end I felt more exhausted than anything else. The orchestra was excellent, and it's a huge one; 8 horns, 6 flutes, etc. I'm still learning to listen to Shostakovich.

The Juilliard school was presenting their annual Focus festival. This year, the focus is on the composer Milton Babbitt and his circle and/or friends. I really like Milton Babbitt's music, though I don't know many people who do. Babbitt was notorious for his many dogmatic and often antagonistic pronouncements about music, as well as being the epitome of the Princeton-based academic composer. His music, however, needs to be separated both from his rhetoric and from its technical origins. To begin with, it is really radical in its approach to time; there are no phrases in the traditional sense, and what we hear is often a seemingly unarticulated continuum. But within that, if the music is properly played, I hear a wonderfully playful panorama of interconnected little motives and elegant melodic fragments. Though often the technical demands of the music are reflected in the performance, which comes out anxious when it really should be relaxed and playful. Babbitt was also known for his encyclopedic knowledge of the American Songbook.

The big piece on the opening concert of the festival was the world premiere of a concerto for violin, chamber orchestra, and tape. (There is a long story behind why it was not premiered until now, you can find it on the internet.) It was a pleasure to hear. The violinist, Julia Glenn, was marvelous and convincing; the Juilliard students in the orchestra acquitted themselves adequately enough to make the piece come across. That said, any Babbitt orchestral work is really beyond the practical reach of any orchestra today to achieve what Babbitt was trying to convey. In other words, it would take enormous amounts of rehearsal time in addition to excellent musicians to fully realize what Babbitt wrote.

It was also great to hear a work by Stefan Wolpe, Chamber Piece No. 2. The rest of the concert, especially an overly long world premiere of a work by Alexander Goehr, was not very interesting. I would have much rather heard more Babbitt.

We also heard the final program in the festival, performed by the Juilliard Orchestra and conducted by Jeffrey Millarsky. It was brilliantly conceived program, beginning with an orchestration of one of Brahm's last works, an choral prelude for organ. This led very well into a performance of Schoenberg's early expressionist work, "Five Pieces for Orchestra". This work is rarely performed, and I don't know why. (Well, I do, it is because it is by Schoenberg, Mr. Box Office Poison himself.) These are extremely colorful and relatively brief pieces; shocking at the time for their lack of tonality, but these days, not too much different in surface texture from what you might hear in a modern orchestral movie soundtrack. It was wonderful to hear them. They are the only purely orchestral works of Schoenberg's expressionist period; the others, like "Erwartung" are vocal works.

The next piece was Stravinsky's "Huxley" variations, rarely heard in the concert hall (like most of late Stravinsky), but I have heard it performed frequently with NYC Ballet's performance of Balanchine's choreography to the music. A model of concision and complexity, it was compelling; I wanted the orchestra to play it again immediately. And it set up the next piece, the even more complex piano concerto by Babbitt. This was Babbitt at his best (or worst, depending on your preferences). What I said for the violin concerto applies equally well here. Babbitt doesn't do overt large scale structures or dramatic contrasts; it's all in the details. There are no obvious rhythmic pulses. I hear intervals and fragments of juxtaposed motives ricocheting across musical time in manifold (that's a favorite Babbitt word) ways. The music demands close listening.

It really is radical avant-garde music; I wonder how it would have been received had Babbitt been some loft-dwelling associate of the abstract expressionists in the 1950's rather than a Princeton professor.

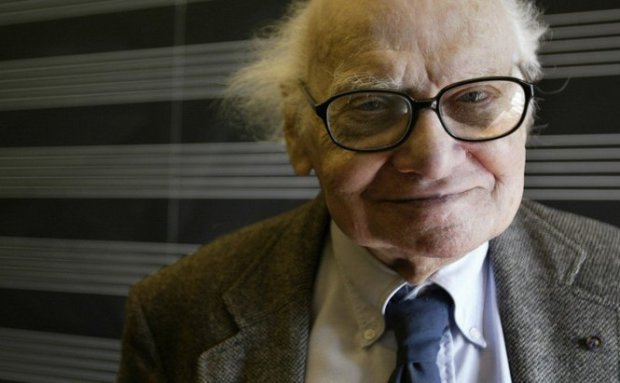

(photo from the internet)

There was one final concert in our string of twentieth and twenty-first century concerts, that of the Curtis Institute Orchestra and Carnegie Hall. They were playing a landmark of the 1960's, Berio's "Sinfonia", along with Busoni's "Berceuse Élégiaque" and Mahler's first symphony. Ludovic Morlot was the conductor. Unfortunately, the Berio was a flop, because we couldn't hear the voices. The piece is composed for symphony orchestra and eight solo voices. In the score, Berio diagrams the placement of the singers (directly facing the conductor) and specifies that the voices are to be amplified, at a level commensurate with that of the other instrumental groups. The vocal sounds include spoken texts, sung syllables, and singing texts. We heard virtually none of this; the singers were seated in the middle of the string sections, and the amplification was too weak to make them heard. This was a real disappointment! It was fine to hear the orchestral part of the work, but we certainly didn't hear what Berio wrote. The Busoni was quiet and enigmatic. (I've heard the Schoenberg arrangement for chamber orchestra many times.) And our resident Mahlerian approved of the performance of the Mahler; it was not the Berlin Philharmonic, but they were pretty good, and the acoustics of Carnegie Hall made everything sound spectacularly beautiful and clear.

No comments:

Post a Comment